This was prompted by a somewhat screamy LinkedIn post about EU AI Act scope and what that means for potentially impacted organisations. I'm not going to share that here, but to paraphrase: All of your machine learning systems, algorithms, and even spreadsheets have to be thoroughly vetted.

Of course that's not true. It came from a management consultancy with an AI governance tool. This is a good run down of scoping criteria from Beachcroft, a law firm. We can make this as hard or easy as we want if the EU AI Act applies to us, but more to the point, we should be doing more than we are to help folk understand what we mean by 'AI' and what that means for them.

People in this space are mostly not systems governance novices. Feelings about the latest big EU tech law are incredibly mixed. At one end of the spectrum arguing it will kill all innovation, at the other evangelising uncritically about the need for unquestioning compliance. Neither is helpful.

Most firms have three pots of potentially in-scope systems:

- Generative AI - The iteration of 'AI' that accelerated this whole circus - definitely in scope, with selective caveats and classifications.

- Other machine learning - systems that infer information to support or make decisions - in scope, but also with a range of caveats and classifications.

- Algorithms that follow strict rules-based logic to support or make decisions - also potentially in scope depending on the context (how and where implemented) - again, repeat after me: with caveats and classifications.

Is that storing up a whole world of pain for lots of businesses? Potentially, yes. Is there an army of more or less specialist governance people poised to offer the equivalent of temporarily effective but dependence enhancing drugs? Absolutely.

What do do:

Descope diligently

Find and quickly descope, with recorded justifications, obviously low risk things. If those things grow legs, arms, and far more complex elements, then triage again and do more to them. Good faith effort that regulators will recognise.

Stop the bleeding

Find generative AI use cases, uplift AI literacy so the whole organisation can help with that. It is great to combine those activities. A great twofer on work that's needed - GenAI will remain a first regulatory focus.

Paint the pre-existing picture

Chat to the teams maintaining and using other machine learning and algorithms to initially scope on a comparable basis. IT, data science, customer services, security, finance, marketing, HR, plus other business functions doing lots of data monging.

Log and plan to review edge cases

Park and set out a process to review in-doubt edge cases. Start that when the EU releases more useful guidance on what scope is and isn't.

Or check out the work you did and records you created in previous similar situations. This is not as novel as folk are painting it. Panicking and saying 'shan't' or 'EU bad' is not going to help.

Worth asking some simple questions?

- Should we know what systems are doing?

- Should we know who and what they impact?

- Should we know how that happens?

- Should we have a good idea of potential issues?

- Should we know how to investigate problems?

- Should we monitor to rapidly spot potential issues?

- Should we feed that back into development, procurement, and strategic plans?

- Should we be transparent about that with people potentially impacted?

Try answering an emphatic 'No!' to all those questions and then consider conditions to make that acceptable. For credit scoring, for benefits entitlement assessment, for customer service routing to a human, for predictive pricing, for targeted advertising, for staff performance monitoring - just a few likely non-generative AI examples that may not historically have had great oversight.

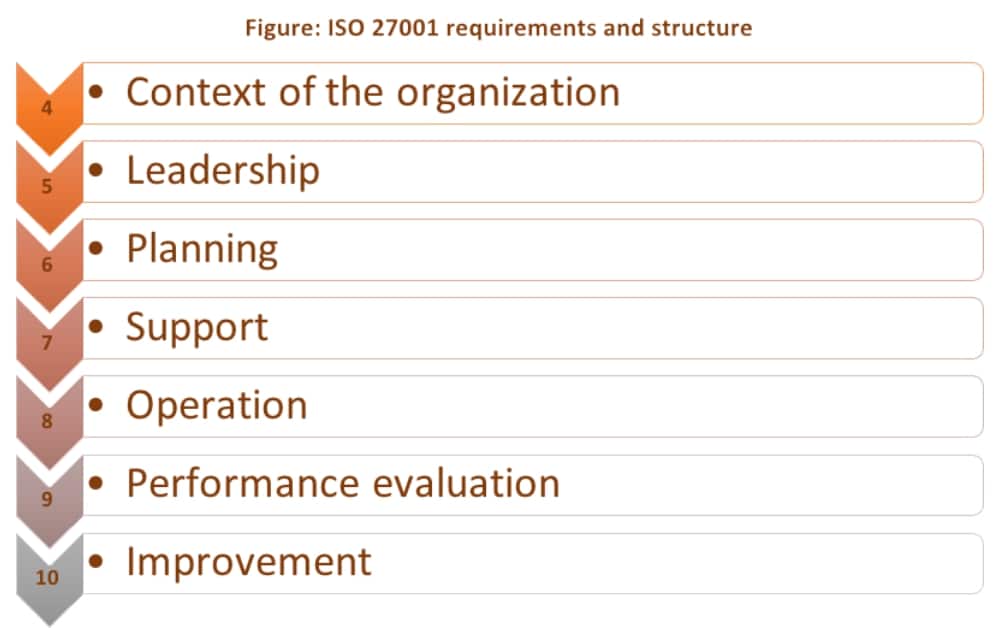

Having an answer to show and tell is pretty much the scope of the EU AI Act and most other standards like ISO27001 - for an Information Security Management System, ISO42001 - for an AI Management System, NIST AI Risk Management Framework, and basic GDPR governance. Any kind of home grown tech oversight will involve tackling those questions.

Show willing, have a first stab at defensible scoping (and descoping), with workings out noted. Show you have some clue about the systems that exist in your organisation and the data that powers them. All rudimentary first steps that you may be sick of repeating whenever a new law or regulation surfaces.

Here's a secret - the things that drive the scoping, categorisation, and prioritisation for deeper dives are substantially similar for each bite of this cherry. The EU AI Act is no different. You would not believe that if you get the gap analysis pitch from a large consultancy with AI-centric branding (yes you sense historical frustration). Building out data and system inventories and maintaining them is the nemesis for most organisations, but that is how you avoid reinventing wheels and generating busy work in these situations.

Now that is a killer AI / ML use case and many other folk know that. In fact some of the most robust proposals for machine learning in combination with a bit of generative AI are in the governance space. Ways to gather, monge, wrangle, continuously monitor, and more usefully maintain all this data.

Of course it is not quite that simple and even those asset inventory applications have their own trade offs, mainly in terms of what they can and can't categorise reliably and all the local knowledge necessary to tune them.

That, I argued here, is the oft ignored part of this equation.

It comes down to the fact that you cannot be pragmatic until you feel the edges of requirements (and the things those requirements apply to). At that point you can differentiate between screamy demands to do everything to all the things Vs reasonable guidance. That has to reference local context. General purpose AI vendors and the regulators lifting things up to be broadly applicable have no idea about your network, data, and real-life AI / ML usage.

There is also this key point: Are regulators coming for firms that make a good faith effort, or those that dig their heels in? What we mainly need is to make that effort less burdensome, especially for firms who do not have the luxury of related in-house skills and experts. That has always been a core focus.

Just a few things to muse on.